This week’s post is devoted to the search of Jupiter’s lightning bolts (aka gamma-rays from dark matter), the construction of new astrophysically-motivated black hole mass function and subsequent search for the black hole mass gap, and a (unusual for this blog, I know!) philosophical discussion on the anthropic principle.

#1 2104.02068: First Analysis of Jupiter in Gamma Rays and a New Search for Dark Matter by Rebecca Leane and Tim Linden

This is a super cool paper which, in the authors’ words, “searches for King Jupiter’s lighting bolts!”, where King Jupiter is a reference to Jupiter/Zeus being the king of the Roman/Greek gods, and lightning bolts refer to…gamma-ray signatures from dark matter (DM) annihilating to long-lived particles (as in so-called boosted DM scenarios) which later decay into photons. The overall underlying physics is not new, and has been applied to many other celestial objects, including of course the Earth, the Moon, the Sun, Mars, Uranus, Neptune, and even exoplanets (as in a recent paper by Leane and Smirnov)! The basic idea is that DM can be (gravitationally) captured in these celestial objects. If captured in a sufficiently high number, it can then annihilate and lead to observable electromagnetic signatures. Jupiter, however, had never been analyzed in this context, where studies have mostly focused on the Sun. This is perhaps surprising, given that Jupiter offers significant advantages over other bodies, since: a) unlike the Sun, it can be used to probe MeV DM (on the other hand, DM with mass below ~3.3 GeV will “evaporate” from the Sun), b) Jupiter is heavier and has a larger radius than other planets, meaning it can capture more DM, and c) being the closest giant planet to Earth, Jupiter should also lead to the largest DM signal. This makes Jupiter an ideal DM detector, especially for light DM.

In this week’s paper Leane and Linden, two experts in indirect searches for DM (particularly in the context of the Galactic Center excess, which to date remains a debated but still possible sign of DM), use data from Fermi to perform the first dedicated gamma-ray analysis of Jupiter. For DM masses above 30 MeV, they set an upper limit on the DM-proton scattering cross-section of about 10^-41 cm^2, up to 10 (!!!) orders of magnitude tighter than limits from direct detection experiments (e.g. XENON, CDEX, PandaX, LUX, CRESST). These limits are subject to some modelling uncertainties, particularly regarding Jupiter’s interior, and, while model-independent, may not apply to specific particle DM scenarios. Nonetheless, it is a very interesting proof-of-principle for the use of our largest neighboring planet as a DM detector. Leane and Linden also find two interesting excesses in their data. One has a low significance, but below 15 MeV there is >5 sigma evidence for excess gamma-ray emission from Jupiter. Before jumping to overly-exciting conclusions, Leane and Linden note that this excess is not well fit by any DM model, and is most likely a signature of cosmic-ray acceleration in the atmosphere of Jupiter. Moreover, the energy bins in question lie pretty much at the edge of Fermi’s effective energy range, so it could very well be an instrumental systematic. However, these result definitely warrant follow-up studies of Jupiter with upcoming MeV telescopes such as AMEGO and e-ASTROGAM. Worthy of being checked out is also the fancy Medieval-ish drop cap at the start of the first paragraph of the paper (see below)!

Credits: Leane & Linden, 2104.02068 (first paragraph)

#2 2104.02685: Find the Gap: Black Hole Population Analysis with an Astrophysically Motivated Mass Function by Eric Baxter, Djuna Croon, Sam McDermott, and Jeremy Sakstein (alphabetical)

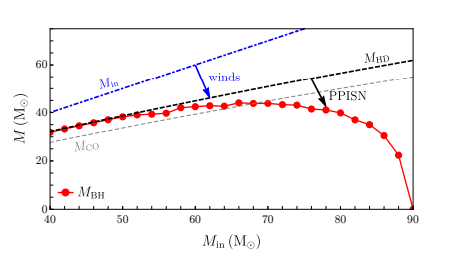

The black hole mass gap (BHMG) is a region of BH mass parameter space where one does not expect to find BHs. In the words of the authors, this is an “unpopulated space in the stellar graveyard”. In the standard scenario, the BHMG is expected to lie roughly between 45 M⊙ and 120 M⊙. Why does the BHMG exist in first place? If a star is massive enough, it enters a zone where electron-positron pair production from the plasma reduces photon pressure. This destabilizes the star, resulting in a so-called pulsation pair-instability supernova, which ejects most of its mass and ends up as a lighter BH. If a star is even heavier, it simply ends up as a pair-instability supernova, which leaves no BH remnant. Excitingly, one can try to use the location of the BHMG (or more precisely its lower edge) as a signature of new physics, the rationale simply being that new physics beyond the Standard Model can alter the physics of pair instability (for instance accelerating the associated processes), which in turn will alter the BHMG lower edge. Examples are discussed for instance in 2007.07889 by a similar group of authors, and the figure below is also helpful.

Credits: Croon, McDermott & Sakstein, 2007.00650 (Fig. 1, right panel)

Current studies of BH populations are mostly based on phenomenological mass functions. The goal of this week’s paper by Baxter and collaborators is to develop a BH mass function which more realistically accounts for the physics of star formation and pair instability supernovae, with as small a number of free parameters as possible. The result is essentially their Eq.(3), where the three parameters are: M_BHMG being (no surprise here) the location of the BHMG, a controlling the sharpness of the mass function peak, and b controlling the event rate as a function of mass. They then go on to constrain M_BHMG from the available LIGO-Virgo GWTC-2 catalog, finding M_BHMG = 74.8^+4.3_-8.0 M⊙. However, this result is strongly affected by GW190521, a binary black hole merger event whose two merging BHs ostensibly lie within the BHMG, with masses of about 85 M⊙ and 66 M⊙. Removing GW190521’s BHs and repeating the analysis, they find M_BHMG = 55.4^+3.0_-6.1 M⊙, a result much more in line with the standard expectations. While we wait for further indications as to the true nature of GW190521 (which could be a straddling binary, or an indication of new physics, as suggested by the same authors in 2009.01213), the mass function presented in this paper will be an extremely useful (and I should say very transparent) addition to the literature, in the quest towards improving our understanding of BH populations and exploring the “stellar graveyard”.

#3 2104.03381: The Trouble with "Puddle Thinking": A User's Guide to the Anthropic Principle by Geraint Lewis and Luke Barnes

For those of you who have been following my blog from its inception (or nearly so), you’ll notice that it’s the first time a paper like this one, much more on the philosophy of physics side rather than physics itself, is featuring. I’m generally not into philosophy in general, as I have no shame in admitting that I find it dull and somewhat of a, you’ll excuse my profanity, “mental wank” (this idiom, while rarely used in English, exists in both Italian and Spanish, so I didn’t just make it up). However, the anthropic principle has always fascinated me, so I was instantly drawn to this paper when I saw the title on the arXiv today. The anthropic principle, oversimplifying quite a bit, is a group of principles which take as starting point the fact that we exist here, today, to observe the Universe. This is then used to work backwards and determine, or rather constrain, the conditions allowing for us to exist today. Unsurprisingly, even minuscule changes in the physical laws or values of the physical constants don’t allow for intelligent life to have formed by today, and is therefore necessarily excluded by the anthropic principle. Exaggerating a bit, but not too much, I’ve always thought of the anthropic principle as somewhat of a boundary condition problem, where the boundary condition is that we exist at redshift z=0 - or as a final value problem, since we are setting a final rather than initial condition. This sounds perfectly reasonable, right? Unless you’re one of those willing to argue that life is an illusion or a dream (as some philosophers in the past have done, e.g. Plato and Descartes), but that’s of course a different matter.

Despite the anthropic principle seeming at first glance perfectly reasonable, many people in the field frown when hearing this name, arguing that it just trying to place humans at the center of the Universe again, and that it is somewhat akin to “teleology, theology, religion, or anthropocentrism” (verbatim from the abstract, as if there were anything wrong with any of these - seriously!). In this week’s paper, Lewis and Barnes essentially argue that the anthropic principle is none of these. It is not religion in disguise, on the contrary one could argue it is a necessary part of cosmology. In its simplest incarnation, the anthropic principle is not saying that we are special or privileged, but is just taking our existence here, today, as a simple fact to be explained. Isn’t explaining observations what science is all about? Surely if you think that it is not worth trying to explain why we are here, today, aren’t you somewhat contradicting the scientific approach? Or, at the very least, being a bit close-minded? Lewis and Barnes also present a historical perspective on developments on the anthropic principle, and argue somewhat between the lines that the anthropic principle started assuming a negative connotation because people started deviating from Carter’s original weak and strong anthropic principles. The finger is pointed in particular at Barrow and Tipler’s strong and final anthropic principles, the latter of which does somewhat place humans at the center of the Universe. I feel there is nothing wrong with this, in principle. It is just a stronger assumption than the mere observational fact that we are here. But don’t we make assumptions everyday in cosmology (6-parameter LCDM, cosmological principle, ergodicity - you name it!)? The important thing is to state what assumptions one makes and how these influence one’s conclusions. In any case, Lewis and Barnes argued that “confusion was inevitable” in light of this deviation from Carter’s original ideas. In their words, “Carter’s important and necessary idea has become both associated with disreputable and speculative company. Understandably, many scowl whenever the anthropic principle is mentioned” (I wouldn’t have used such strong words, especially not “disreputable and speculative” since it’s Barrow we’re talking about, but there you have it).

Where does the “puddle” in the title come from? It comes from an analogy in Douglas Adams’ 2002 The Salmon of Doubt, where he compared us to a puddle named Doug, who one day gains consciousness and speculates as to the perfect match between his shape and that of the hole he lives in, jumping to the conclusion that the world was meant to have him in it (this is basically the final anthropic principle, or rather final puddlopic principle), and thus being surprised when the Sun dries him away. Lewis and Barnes argue that a) Doug is right to speculate about his match with the hole being worthy of explanation, b) he is not arrogant to look for an explanation, and c) he would be unwise to dismiss without good reason the supposition that he is made for the hole. I completely agree with these conclusions. The reason I really liked Lewis and Barnes’ paper is that I, too, feel that many in our field are being unwise, arrogant, and somewhat unscientific in dismissing the anthropic principle as unworthy of consideration. “Puddle thinking” is often used as an excuse to dismiss fine-tuning as unworthy of our attention at all, but Lewis and Barnes argue this is dangerous. I feel very strongly about this issue and the associated dismissive behavior, which is perhaps why my language in this post has been a bit stronger and more provocative than usual (which you’ll excuse me for). Note that the anthropic principle is not postulating the existence of a divine being. It’s a different matter whether you believe in one (I do, no problems in admitting that - it’s just not any of the “usual” Gods of the “usual” religions, including ancient Greek/Roman Gods such as Ζεύς/Iupiter).

Addendum: if you enjoyed Lewis and Barnes’ writing, I highly recommend you read their popular science book The Cosmic Revolutionary’s Handbook, published by Cambridge University Press. You can read my review of the book on Nature Astronomy (non-paywalled link) - spoiler: the book is very well written! Lewis and Barnes also hold regular podcast episodes on their YouTube channel, and you can watch their puddle thinking episode here.